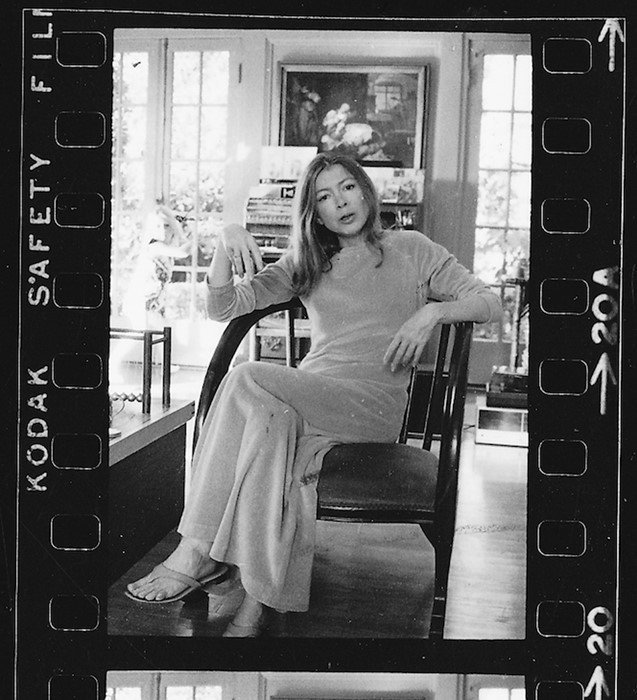

This is the first prose from Joan Didion’s essay White Album. In the essay, Didion describes the moment she could feel the ‘60s “snapping” as she and her husband watched Robert F Kennedy’s funeral on TV from their veranda at the Royal Hawaiian Hotel in Honolulu.

It is uncanny how those times, the late 60s into the 70s, seemed calamitous but inspiring. The counterculture and protest movements were steadfast and resilient. Presidents were still presidential. There was hope for a better tomorrow with a dash of healthy resistance and revolution against “the system.” But Joan felt the tension of the snap. Comparing then to now, depending on what story you are telling yourself, many of us are feeling not only the snap but a full-blown break, and we seem to be sliding down the precipice of the break. The question is, how far down will we go…

In Didion’s essay, she goes further. She writes,

“We look for the sermon in the suicide, for the social or moral lesson in the murder of five. We interpret what we see, select the most workable of the multiple choices. We live entirely, especially if we are writers, by the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images, by the "ideas" with which we have learned to freeze the shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience.”

We work with what we know, value, and believe within the constructs of our lives. These constructs are very different depending on who you are, where you come from, your skin color, your creed, caste, and gender. Your living and lived experience. Yet, we tell ourselves stories—fiction, non-fiction, fairytales, and horror. But many of the stories we hear and tell are informed by the pods, bubbles, and clusters where we associate and engage — for better or worse.

We tell ourselves stories in order to deceive: It won’t be that bad. We have systemic and institutional checks in place.

We tell ourselves stories in order to survive: We’ve seen this rodeo before. We just have to wait it out.

We tell ourselves stories in order to feel sane: But there is nothing sane about any of this. Something is deeply, deeply wrong.

Dear reader, you may be wondering why I shyly refer to storytelling and self-counseling. Let me enlighten you on The Food Archive’s current storyboard: She lives in the United States and is sensing the country’s political state unraveling. But it isn’t just that. It is world order overall, and the shifting winds towards isolationism. It is climate change and the many extreme events impacting so many people, particularly and disproportionately those least responsible for the warming of our earth. It is the lack of political will and wherewithal for industries to do the right thing beyond profit-mongering. It is the dizzying speed of AI, media, and technology—the mis-, dis-, and malformation that surrounds us and our robotic tendencies to let “it/they/them” manipulate and control our every move. And of course, I am profoundly concerned about people’s food security today, tomorrow, and in 2050.

We are leaving 2024 in a very complex, dizzying state of change. Even if you are gleefully happy about the turns happening in the United States, our planet and our place in it is precarious. This poem by Warsan Shire keeps running through my head:

“later that night

i held an atlas in my lap

ran my fingers across the whole world

and whispered

where does it hurt?

it answered

everywhere

everywhere

everywhere.”

Joan Didion felt the same way in 1968, but alas, we are still here, plodding along…So there is that. At least, that is the story I am sticking to.