Climate change is having profound impacts on the ability to grow both foods for humans and feed for livestock. Growing food and feeding livestock, in turn, exacerbates climate change. Livestock raised for beef is responsible for 6 percent of total greenhouse gas emissions largely in the form of methane. Livestock is also the number one driver of deforestation around the world, reducing the chances for large forest biomes to serve as carbon sinks.

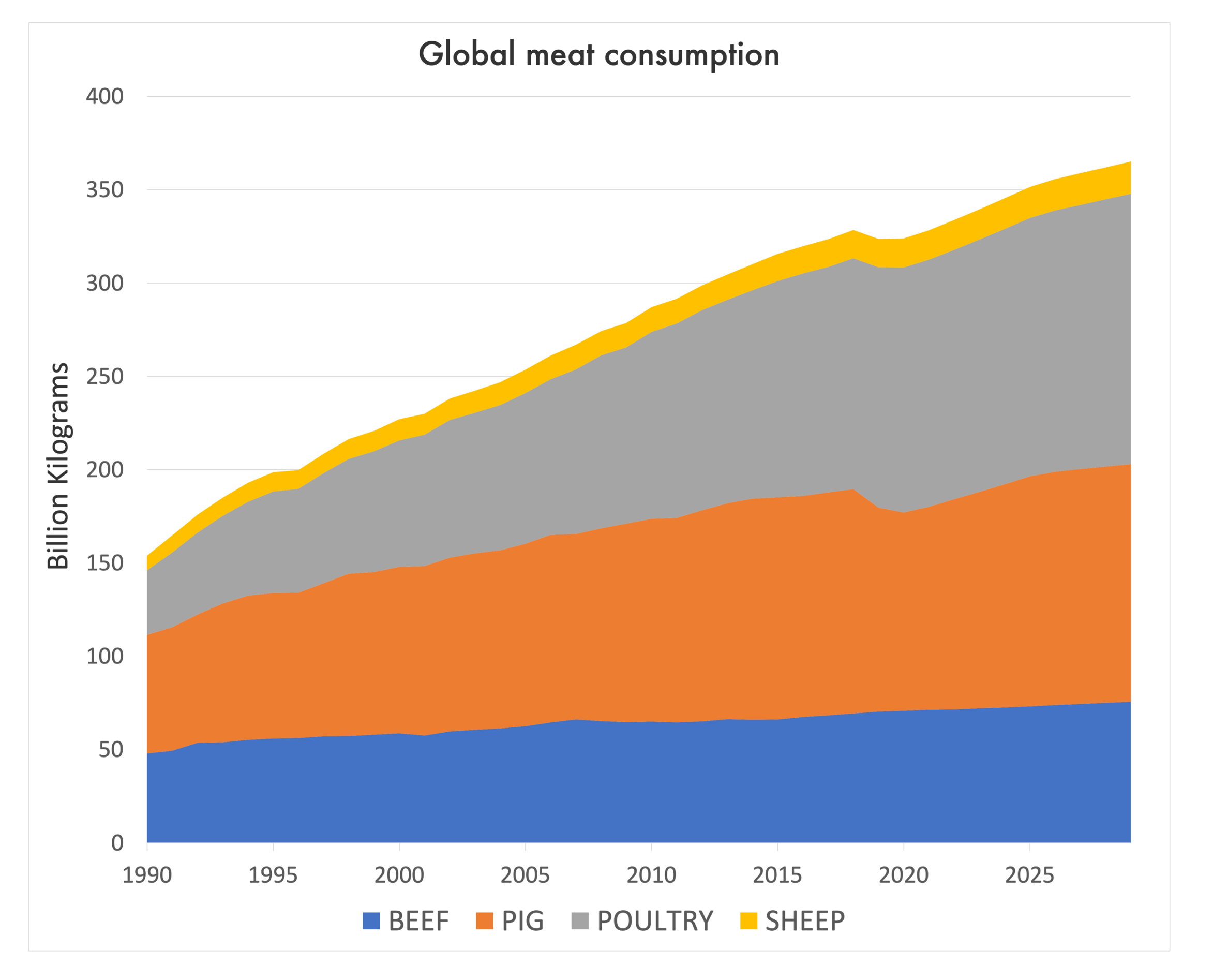

While these stresses continue to rise if no significant action is taken to mitigate climate change, demand for meat is rising all over the world. According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, beef consumption has been steadily rising over the last few decades, and as people become wealthier, the more meat they consume. And people, well, like meat!

Some tech companies have come up with a solution—alternative proteins—which include lab-grown meat, plant-based meat, single-cell proteins from yeast or algae, and edible insects. The lab- and plant-based alternative innovations mimic the taste, smell, and texture of meat and could be significant disruptors, eliminating the need for people to raise or consume animals.

As of now, the products available for consumers are mainly plant-based proteins like Impossible Burger and Beyond Beef. Data suggests that these foods are tasty to most consumers and have lower environmental footprints and greenhouse gas emissions than beef. They also have benefits for those who care about animal welfare.

They are however under scrutiny about their health properties and cost. Some argue these foods are overly processed, with a lot of artificial ingredients to get them to a state of palatability. Beyond Burger has approximately 25 ingredients whereas beef has just one ingredient – muscle tissue. They are also costly. One Impossible burger in Washington DC’s Founding Farmer restaurant costs $17.50 as compared to the all-beef cheeseburger at $14.50.

The products in the R&D pipeline – such as lab-grown meats – will have to undergo significant regulation by governments and there is the issue of scale. In the film, Meat the Future, the company Upside Foods (formerly known as Memphis Meats), which is using cells taken from an animal to grow meat, is challenged in making enough products at scale to feed the world’s growing population. While these are hurdles, there are some glimpses of promise. Those that have tried these products are pleasantly surprised at how similar they taste to the real thing and issues of scale are just temporary roadblocks.

Yet, will consumers accept and embrace these foods? The backlash against genetically modified foods shows early signs of what may come as companies begin to get lab-grown meats to market. Many consumers may argue these foods are fake and may be hesitant about their food being “grown” in Petri dishes.

The big issue is, that we may not have a choice but to eat lab-grown meats. It will be very difficult to raise livestock in a hotter world. Not only will feed and water be scarce, but hotter climates wreak havoc on the health of the animals. These projected adverse effects will put premiums on the price of meat in the grocery store.

So while the world can be picky for the time being, these new foods may become our mainstay survival foods because they may be the only option. To ensure these foods are affordable, accessible, and acceptable to consumers all over the world, and not just curious rich people, several things need to happen.

First, companies producing these foods need to ensure transparency in how these foods are produced, and their impacts across a broad range of outcomes, particularly health and nutrition. There is a need for transparency regarding their nutritional content that is easy for consumers to understand and find. Companies should take lessons from how genetically modified foods were communicated and the fears and doubts they have raised among consumers.

Second, for those products that have unhealthy ingredients with losing palatability, the companies should work hard to reformulate the products to decrease the content of sodium and unhealthy fats. They should also work to fortify these foods with adequate micronutrients.

Third, these foods should be low cost, or real meat should be more expensive, keeping with the true costs to produce beef. As the demand for these alternatives increases and more companies come on board with new products, as with any economies of scale, the price will come down.

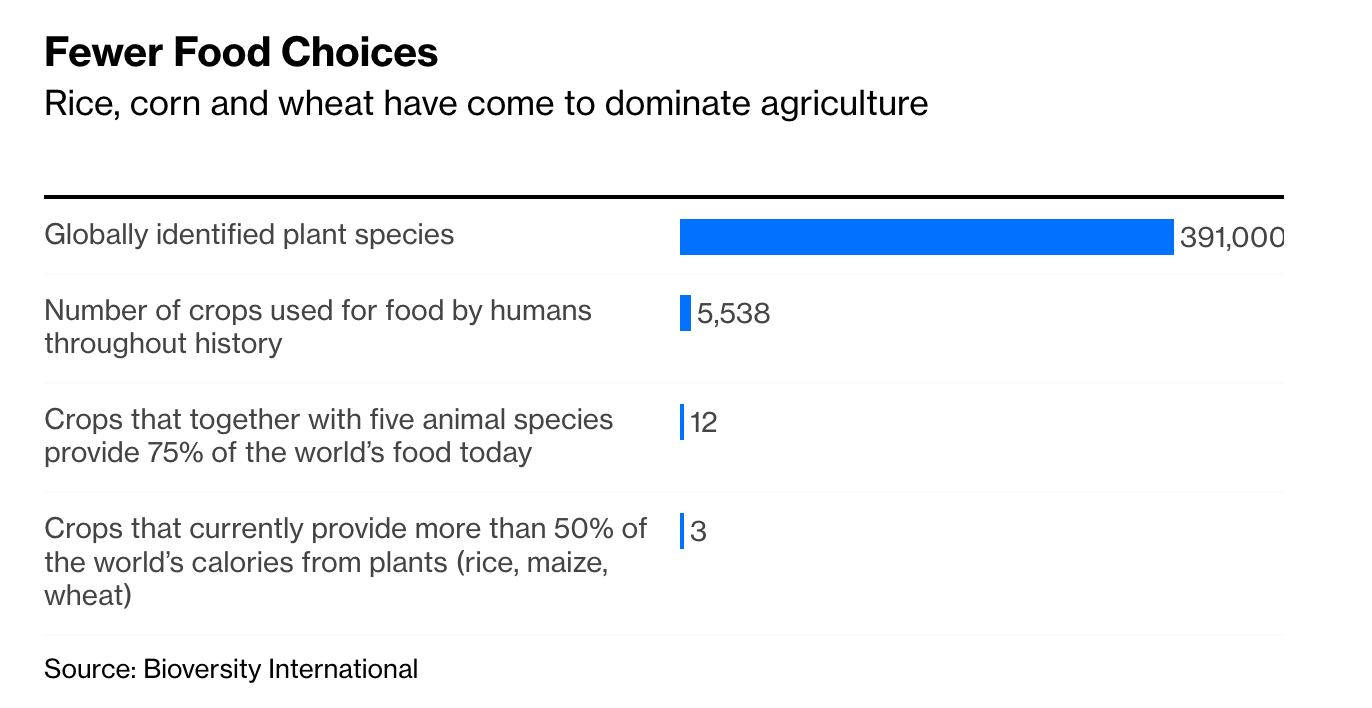

Last, while the innovation for these new foods is tempting, there are many traditional foods such as legumes, insects, and algae that have important nutritional value, particularly protein, have low environmental footprints, and do not require raising animals. These traditional foods, while traditional, may offer low-cost, low-resources alternatives to shiny and new future foods.