FOOD BYTES IS A (ALMOST) MONTHLY BLOG POST OF “NIBBLES” ON ALL THINGS CLIMATE, FOOD, NUTRITION SCIENCE, POLICY, AND CULTURE.

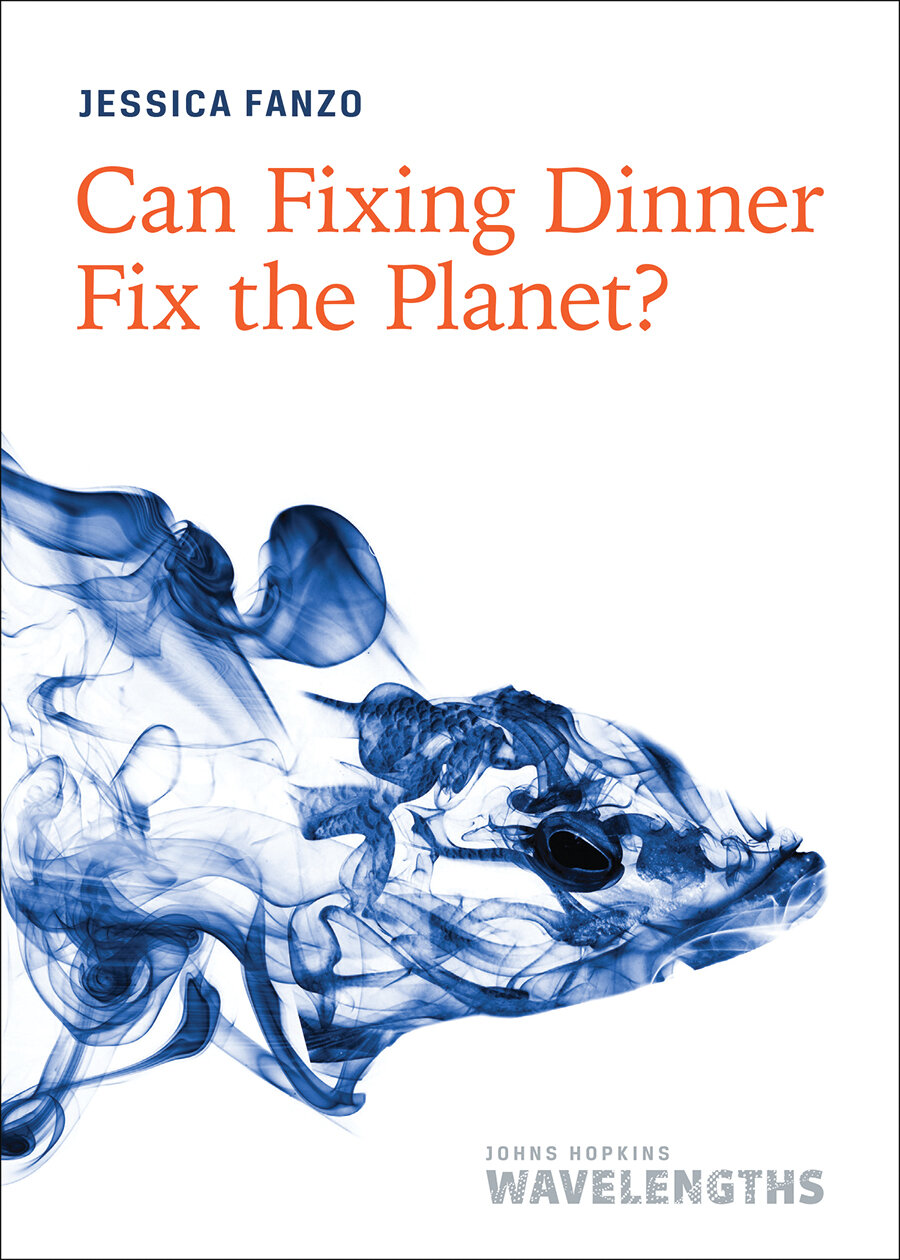

Someone recently asked me, “How do you have so much time to read?” I don’t, but these days, I find myself reading more as a deliberate form of escapism. Amid the current state of affairs, I need to remind myself that a collective continues to believe in science, evidence, and data, and the art of generating and sharing knowledge is not lost. So thank you—scientists, educators, and data generators—for all that you do to keep our world informed. Shine on you crazy diamonds! Let’s round up what The Food Archive is reading and listening to in the here and now.

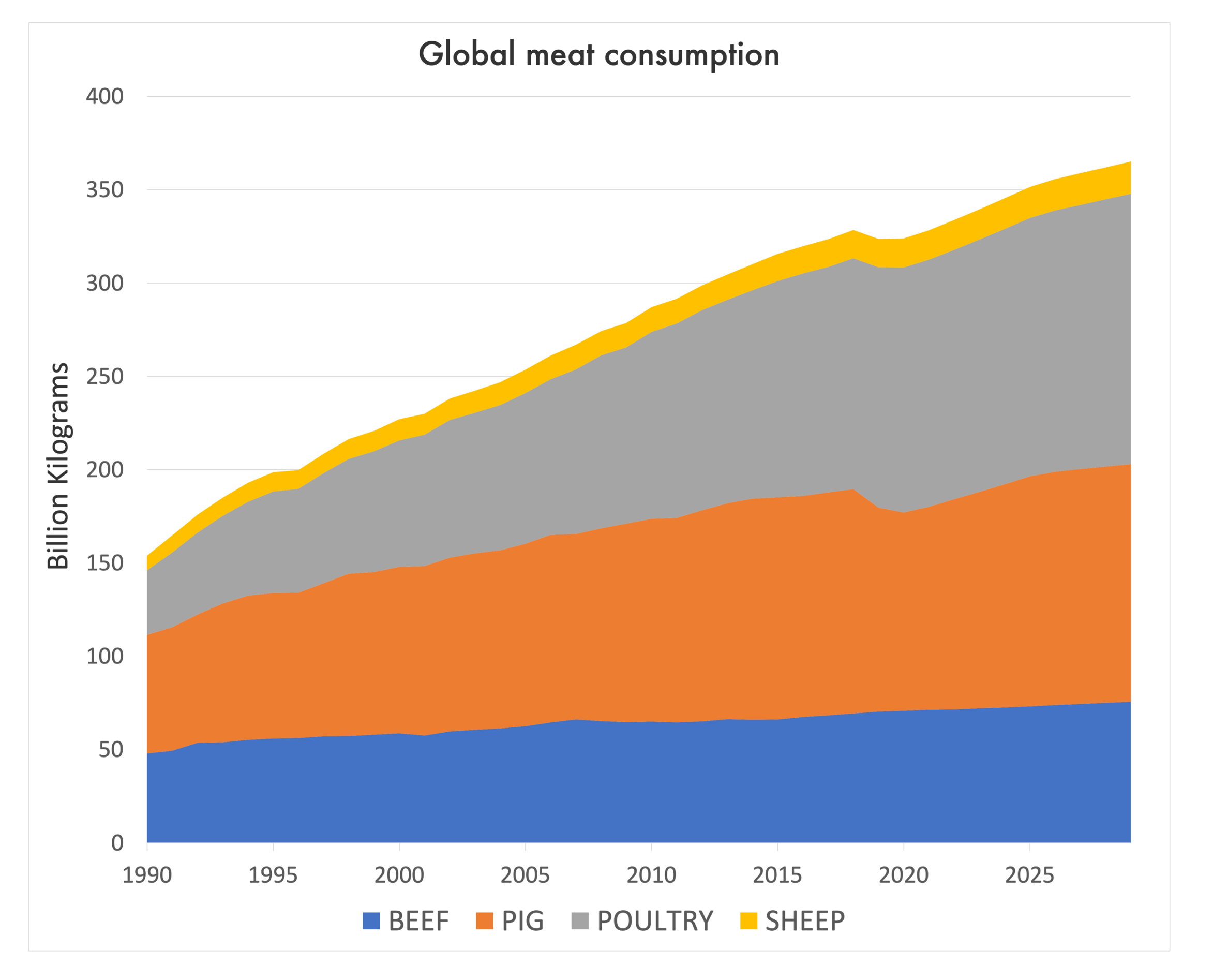

The cost of food, is at the forefront of everyone's mind, including coyotes hanging out in grocery stores in Chicago. Much speculation exists about how the U.S. administration’s tariffs will impact food. For now, let’s put that debate on pause and, again, focus on the generators of evidence. The fantastic Eat This Podcast by Jeremy Cherfas has a recent episode that discusses Bennett’s Law with economist Marc Bellemare — this notion that people eat more nutritious foods (including animal source foods) when they have more disposable income. It is a great conversation, and Marc argues that his latest paper somewhat proves the “law.”

Speaking of cheap food, did you think that McDonalds restaurants could be “pretty”? The lore of design is bringing people to McDonalds. And for those who don’t like the corporate notion of McDonalds flooding fast food to the masses, it seems you lost. Is the New York Times being paid by McDonalds for these article placements? For some deeper dives into fast food, there is always the classic Eric Schlosser’s Fast Food Nation, but I recommend two more nuanced reads — Franchise: The Golden Arches of Black America by Marcia Chatelain, who won the Pulitzer Prize and White Burgers, Black Cash: Fast Food from Black Exclusion to Exploitation by Naa Oyo A Kwate. Both are worth the time.

Analysis by Politico on the hidden costs of food systems to diets in Italy.

Fast food has changed diets, and for some cultures, diets are disappearing (I snatched up the URL in case this trend continues). An interesting article in Politico argues that the Mediterranean diet is a lie, at least in Italy. Having lived there five years, I was always pleasantly surprised that traditional regional cuisines were preserved and revered, however in the confines of how a Mediterranean diet is defined, I didn’t see many diets from the north to south classically fall within that dietary pattern. Italians consume a lot of meat and cheese. The Politico article argues that the hidden costs of the Italian food system and diet do not fare well for health outcomes. Check it out. Speaking of Italian diets, I guess pasta is not a refined or ultra-processed food. Whew. I guess I can continue to eat my spaghetti ala vongole every Friday and not die at 55… The Japanese diet, a fish-dominant diet, is changing too. According to Grist, veganism is increasing.

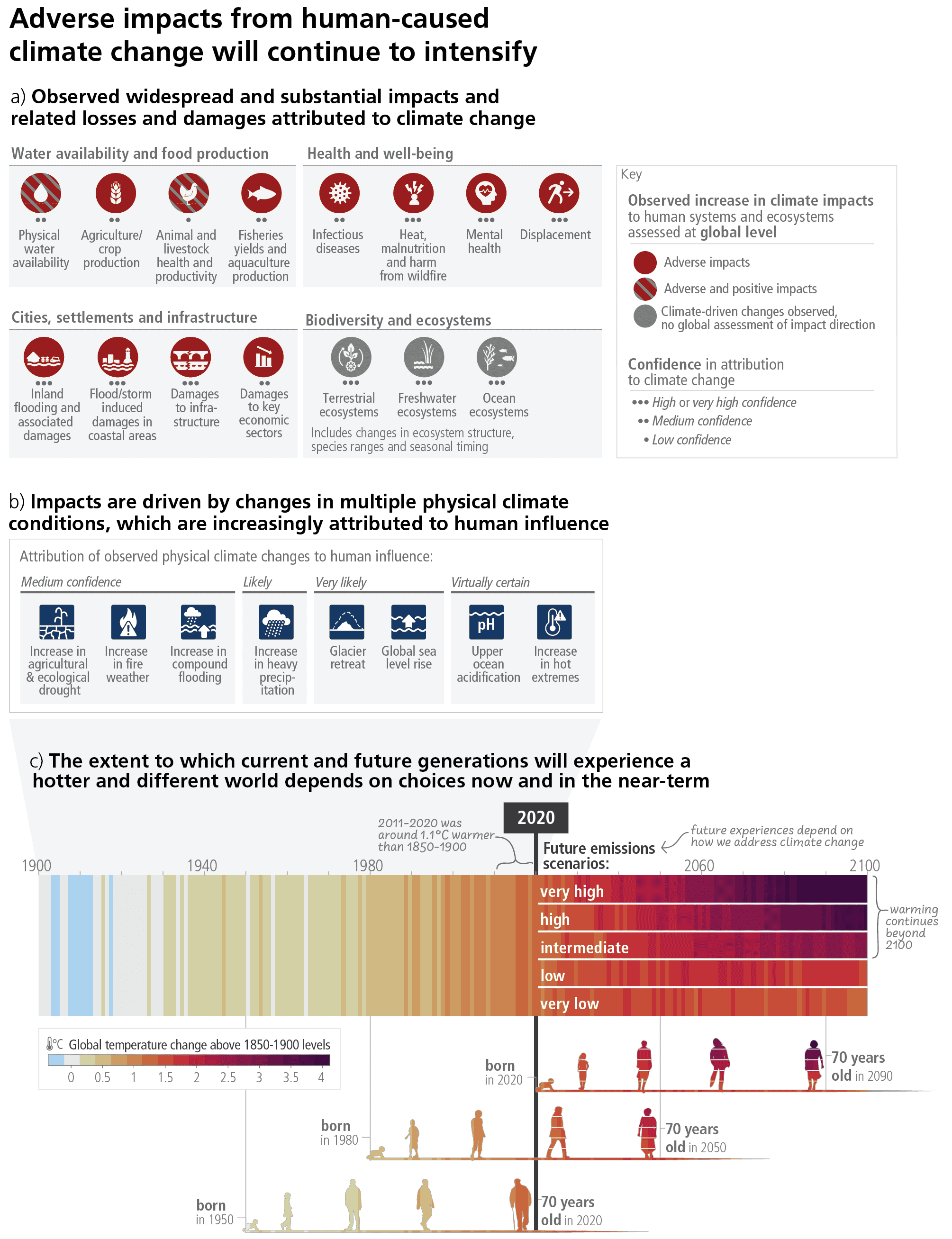

Some lovely and alarming science is being generated about how our agricultural system will feed the world. According to colleagues at Tufts University (hey Will!), while food supplies are, in aggregate, fulfilling calorie needs, they are not fulfilling healthy calorie needs. Food availability of fruits, veggies, legumes, nuts, and seeds (the core makeup of a healthy diet) falls short worldwide. Regionally, there are considerable disparities in the supply of animal foods. We also have issues with water. This article in Nature Comms by scientists across the world (hi Kyle!) examined blue water, which is surface and groundwater often used for growing crops. They looked over time from 1980 to 2015 in China, India, and the US. They found that demand has risen significantly for blue water by 60%, 71%, and 27%, respectively, for a handful of crops, largely alfalfa, maize, rice, and wheat, and this rise in demand has created issues of scarcity and stress. Good times! According to Carbon Brief, we shouldn’t just be worried about water either. Extreme weather is destroying crops around the world. Check out their map and analysis (see below). According to colleagues at Purdue University (hi Tom!), all hope should not be lost. They examined the impacts of improved crop varieties since the early 1960s and argued that these crop improvements resulted in lower land use change, greenhouse gas emissions, and cropland expansion. Let the debates begin! And what is a summary of feeding the world and improving crop varieties without AI. A new outfit, Heritable Agriculture (sounds so down homey!…), wants to use AI to predict genetic changes to improve crop yield, taste, nutritional value etc, etc. No need for future Borlaugs of the world!

Map developed by Carbon Brief on extreme weather events impacting crops in 2023-2024

Food systems remain political monoliths, and many newly published papers focus on how to get over political inertia. Two new papers by Costanza Conti unpack top-down and bottom-up approaches to transforming food systems and how to better integrate or consider justice in strategizing, implementing, and monitoring food system transformations. A paper by Patrick Caron argues in a new Nature Food commentary that disagreements stymy action on food system transformation. He and several others have begun the Montpellier Process, which “promotes safe spaces for risk-taking, where citizens, decision-makers, economic players, and academics can compare their perspectives, share knowledge, address controversies, learn from one another, and explore potential solutions.”

Speaking of politics, a timely paper in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, including Editor-in-Chief Chris Duggan, argues that dismantling USAID and the withdrawal from the WHO by the current U.S. administration is catastrophic for global nutrition and health. In their conclusion, they wrote:

“The events of 2025 have dealt a catastrophic shock to international nutrition research, programs, and cooperation. Nevertheless, there are important questions about the status quo. The present crisis has drawn into sharp relief the global health and nutrition communities’ reliance on US funding. In addition, there have been growing calls for more equitable systems of scientific collaboration and programmatic decision-making.”

Here we are readers, …I believe we need to make some hard pivots based on these new realities and strategize in very different ways. Meanwhile, those of us in research and academia will keep the lights on, diligently documenting what we see in the world, why the world is the way it is, and what we can do about it, at least, scientifically speaking.

See ya’ll in March!