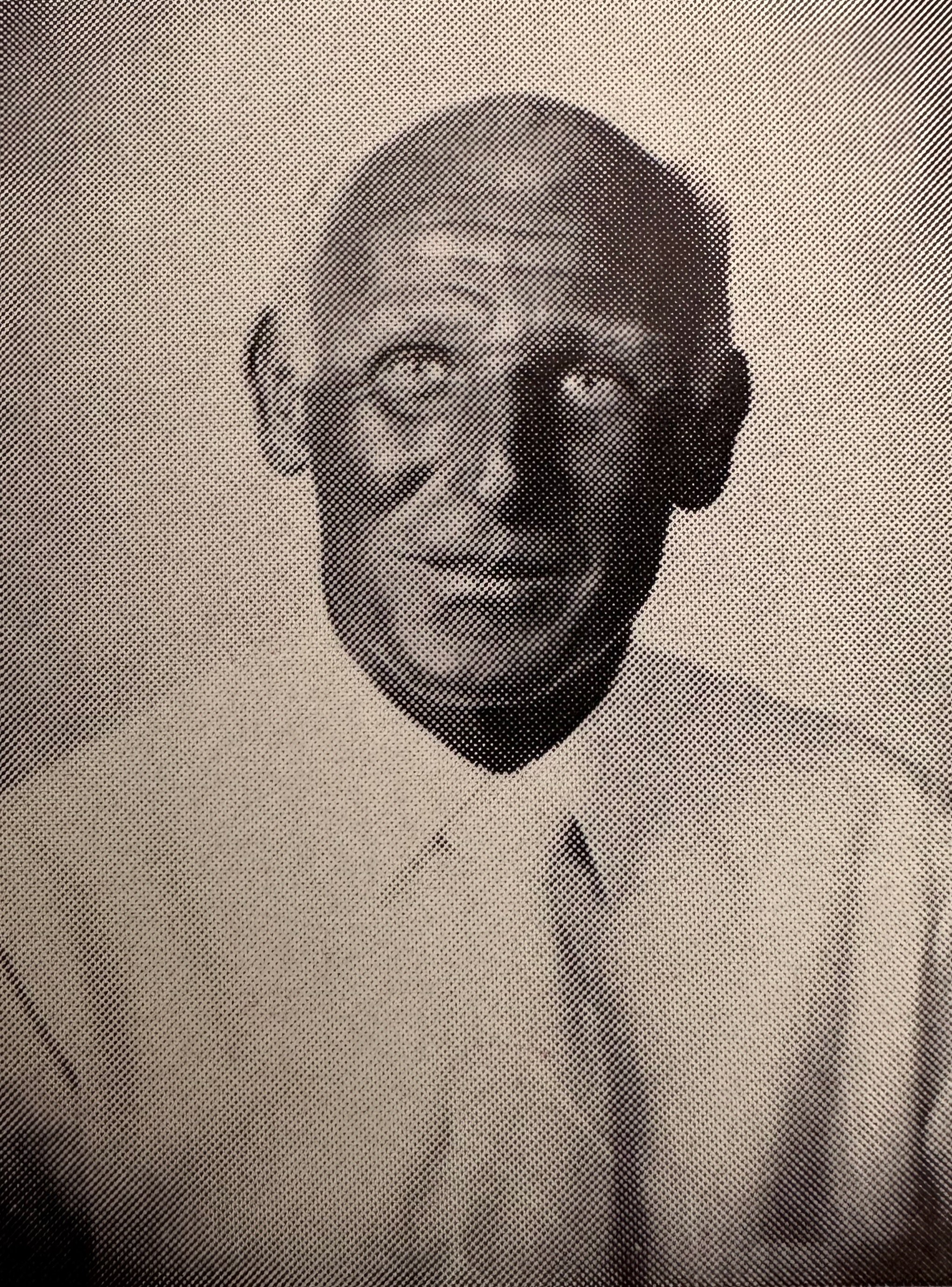

The only photo I have of Doc Zinke from my high school year book…

My relationship with science began with struggle. As a student raised outside the scientific milieu, I found myself grappling with the core concepts of biology and physics. Yet, my trajectory shifted unexpectedly during my junior year of high school, thanks to Doc Zinke, my chemistry teacher. Despite his diminutive stature, he possessed an extraordinary ability to animate the often-abstract world of chemistry. Through engaging stories and real-world applications, he revealed science as a lens through which to view and understand the world. Although my grades did not immediately reflect a profound grasp of chem, Doc Zinke instilled in me a lasting appreciation for scientific inquiry.

Since that pivotal moment, science has remained a central theme in my life. My academic pursuits led me to a bachelor's degree in agriculture and a Ph.D. in nutrition. As a professor, I am privileged to be constantly immersed in the world of science. My partner, a mathematician, physicist, and writer, shares my conviction that data, evidence, and the relentless pursuit of scientific understanding are the primary drivers of progress.

I recognize that skepticism toward science is not unfounded. History is replete with examples of scientific advancements being misused, resulting in detrimental impacts on individuals, societies, and the environment. However, to reject science wholesale due to past transgressions would be a profound error. The current climate of widespread skepticism and the dismantling of scientific institutions, particularly universities, is deeply troubling. Do we not still seek innovative treatments and potential cures for cancer? Are we not compelled to advance agricultural science to feed a growing global population? Do we not recognize the importance of preventative medicines in safeguarding children's health? Does the exploration of space not ignite our imagination and expand our understanding of the cosmos? And, perhaps most urgently, do we not have a moral imperative to understand how to protect the health of our planet and its inhabitants?

Support for scientific endeavors and scientists is paramount, enabling us to describe the world around us and to understand its underlying mechanisms. Science is critical because it empowers us to solve complex problems and to make evidence-based decisions that can improve the quality of life across diverse domains, including food systems, healthcare, environmental conservation, technology, and communication. The cultivation of knowledge and the refinement of critical thinking skills are essential, and we rely on institutions—particularly universities—to nurture these skills in the next generation of scientists.

While science may not hold all the answers or provide an entirely objective representation of reality, it remains one of humanity's greatest collective endeavors. Science contributes to the strength of democracies by generating knowledge and informing solutions in the face of unprecedented challenges. Now, more than ever, we must safeguard science, scientists, those who teach science, and the institutions that support them. Higher education institutions, the National Institutes of Health, and the National Science Foundation are crucial in ensuring that scientific advancements continue to benefit humanity and the world at large.

It seems in all of this freezing and firing chaos, we have forgotten that people are at the root of scientific endeavor, and I want to thank all the teachers and professors out there like Doc Zinke — Thank you for teaching me the enduring power of science.