FOOD BYTES IS A (ALMOST) MONTHLY BLOG POST OF “NIBBLES” ON ALL THINGS CLIMATE, FOOD, NUTRITION SCIENCE, POLICY, AND CULTURE.

I just returned from an unforgettable trip to Lao PDR, with two stopovers in Bangkok, Thailand. Laos is a country of striking contrasts—on one hand, it moves with an unhurried, almost meditative rhythm; on the other, it carries the weight of a complicated past, still navigating the long shadows cast by war, particularly the enduring legacy of unexploded ordnance.

By Jess Fanzo, Luang Prabang

As many of you are aware, I’m currently working on a book that explores how the counterculture movements of the long 1960s have shaped today’s food systems. Inevitably, that journey includes grappling with the legacy of the Vietnam War, and as an American, traveling through this region stirs deep reflection. It's impossible not to think about the imprint left behind by U.S. military action and the resilience of communities who’ve had to rebuild in its aftermath.

Yet what struck me most was how far this part of the world has come. There’s a quiet strength in Laos, a gentle pride in its culture, and a determination to move forward without forgetting the past. It’s a powerful reminder of the world’s ebbs and flows, and how, even in the face of immense hardship, there’s the possibility of healing. “This too shall pass” kept echoing in my mind—not as a dismissal of pain, but as a recognition of time’s capacity to soften and transform.

Onward to this month’s Food Bytes.

IFPRI put out a bible in this year’s Food Policy Report. Where the rubber meets the road is Section 5, on effective change and the factors that determine how policy change occurs. One of our new papers led by Stephanie Walton (who is doing amazing work at Oxford) suggests that addressing asset stranding proactively, rather than trying to prevent it, could be a powerful lever for change.

Some great data exercises are out that provide useful nuance in how our food systems are performing. First up is the Systems Change Lab, which assessed progress for 32 outcome indicators in the food system. To help spur transformational change, we also highlight 58 critical enablers and barriers. Results of their analysis? NOT GOOD. The second is by the Better Planet Laboratory, which identifies food flows through nearly every major port, road, rail, and shipping lane worldwide and traces goods to where they are ultimately consumed. It’s called the Food Twin Map.

There are also some great people producing worthy pieces to read and follow. First, the great Bill McKibben has a Substack. I encourage you to read one of his latest entries, “So many moving pieces.” Nicholas Kristof is fighting the good fight and producing many excellent pieces on how the US government’s actions are harming global health and nutrition. Check out this, this, and this. Other institutions are getting in on the action. Bloomberg News has launched a new food column, titled "The Business of Food." The UNDP appears to be making a play in the food systems sector, including the launch of a new Conscious Food Systems Alliance. Fascinating!

Some highlights from journalists writing about food:

An interesting take on RFK Jr’s Make America Great Again policy: Grocery Update Volume 2, #4: MAHA Or Misdirection. Grocery Nerd argues that the “MAHA” framework may serve more as political window dressing than actual change.

DeSmog reported that food giants Nestlé, JBS, PepsiCo, Mars, and Danone are overstating their climate commitments—leaning heavily on unproven carbon removal schemes, neglecting methane reductions, and relying on weak, loophole‑filled deforestation pledges—according to a new report from the NewClimate Institute and Carbon Market Watch. Gee, what a shocker…

In this article by Grist, the blending of at least 30% vegetables or plant proteins into meat products—known as “balanced proteins”—can deliver taste and price similar to conventional meat, while significantly reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

This fascinating article in The New Yorker, entitled “Schmear campaign: How a Hazelnut Spread Became a Sticking Point in Franco-Algerian Relations,” is about how the European Union has banned Nutella competitor El Mordjene, a move some see as politically and racially motivated.

In the New York Times, they have a new series, “What is History.” They kicked off the series with two articles on food: One by Jacques Pepin on culinary pursuits and the other by Carey Fowler on the biodiversity of our food supply.

I fully admit to being a fan of Elizabeth Kolbert, and she delivers with her latest article: "Do We Need Another Green Revolution?" Worth your time to read along with all of her work.

Michael Grumwald has a new book out, and he wrote a piece, A Food Reckoning Is Coming, as part of his book tour. Another worthwhile and perhaps divisive read.

Some highlights from the science literature

This study validates the Healthy Diet Basket—a least-cost dietary model based on food-based dietary guidelines—as a globally consistent benchmark, finding that it delivers adequate macronutrients and micronutrients at about US $3.68/day.

Whereas this study argues that dietary species richness (DSR)—a measure of the number of different edible species in a diet—is the most effective global marker for capturing food biodiversity. They also show it correlates strongly with lower mortality in Europe compared to other diversity indices, and tracks micronutrient adequacy in low- and middle-income countries.

Speaking of diets, this study uses a linear programming model of over 2,500 U.S. foods to show that individually tailored vegan, vegetarian, and flexitarian diets (with ≤255 g of pork and poultry per week) can meet nutritional needs, align with the Paris Agreement's 1.5 °C climate target, yield up to ~700 healthy-life minutes per week, and reduce climate impacts sevenfold.

Fortification remains essential and is considered a cost-effective way to fill nutrient gaps. Check out this modeling paper.

On processing…This NEJM perspective argues that mounting evidence linking ultraprocessed food consumption to increased calorie intake, obesity, and chronic disease necessitates regulatory policies—such as front‑of‑package labeling, marketing restrictions, and excise taxes—to curb their public health impact. Not sure there’s anything new here.

Numerous modeling papers are being published on the impacts of climate change on food production. This paper models six usual suspect staple crops — maize, soy, rice, wheat, cassava and sorghum — and finds that for every 1 °C increase in temperature, food production will decline from current levels by 120 calories per person per day, but that income growth and adaptation strategies could alleviate 23% of global losses by 2050 and 34% by 2100. Gulp.

Should we consider alternatives like insects? According to this article, that may not be the case. The title alone is click-worthy: Beyond the buzz: insect-based foods are unlikely to significantly reduce meat consumption.

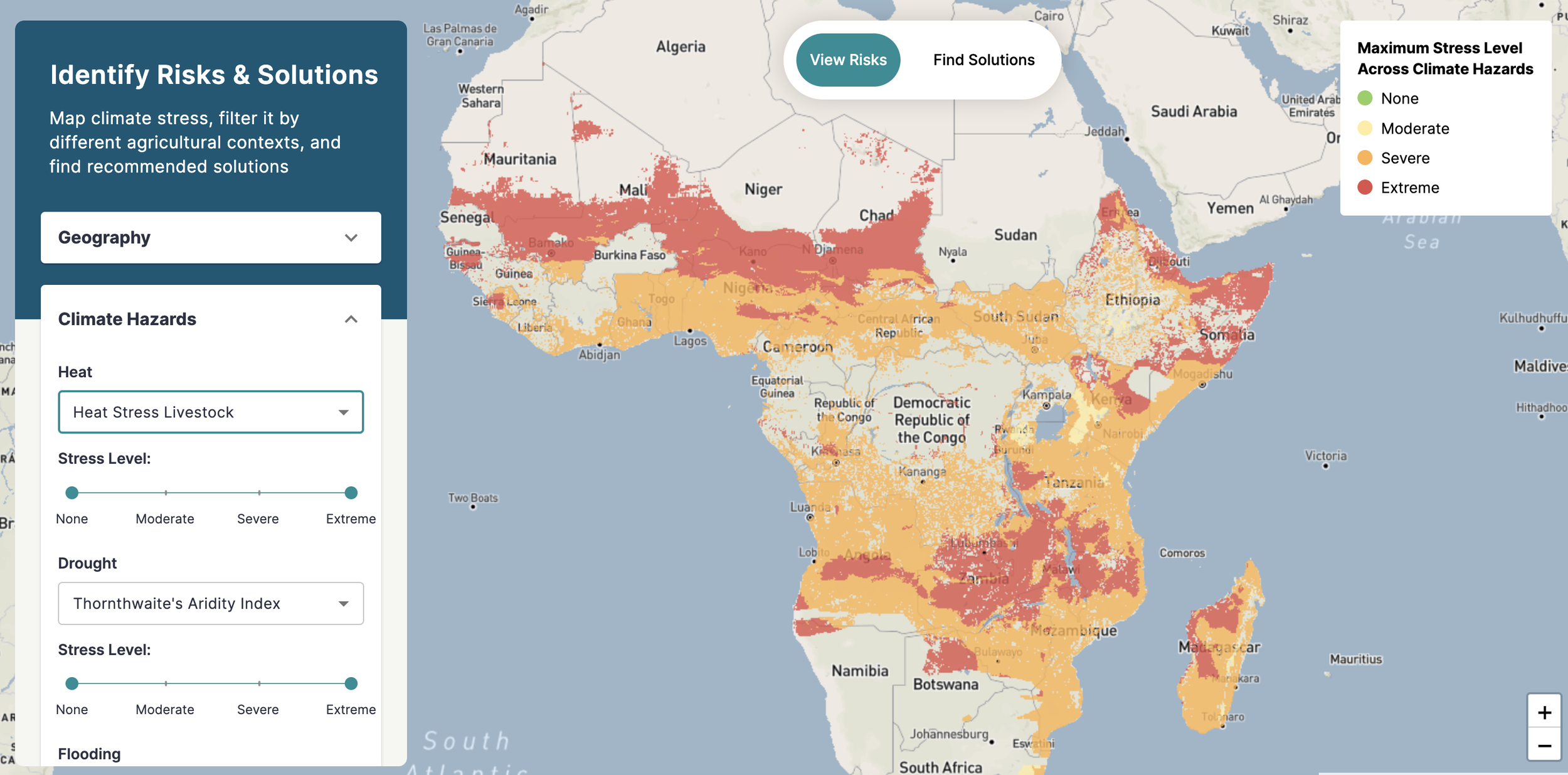

Maybe it’s time to start building climate-resilient systems - not just food, but across all systems. Check out our new policy paper, which argues in this manner.

For those interested in broader development issues, the Sustainable Development Report 2025 is now available. Another report that feels more like a book on how the world is progressing on those pesky goals that would make the world a better place and leave no one behind. Related to that, we have a new paper on how pastoralists are coping with resource constraints, conflict, and climate extremes. We initiated this work a decade ago in Isiolo County, Kenya, utilizing photo elicitation and semi-structured interviews with Borana and Turkana pastoralists to gain a deeper understanding of the constraints hindering their ability to practice pastoralism and to identify opportunities for better supporting pastoralist communities with climate-resilient strategies. And last but not least, a conversation about The Myth of the Poverty Trap.

And do check out our new Food for Humanity podcast! This limited series is all about alt-proteins.

That’s all, folks. Have a wonderful, safe, and delicious summer!