I usually don’t take a vacation in the summer because of the expense and the crowds, but I went against the grain, and we took a trip to America’s great western expanse. My partner and I spent many years growing up in the West, and it has always been a place that resonates in our genes. Our holiday started in Santa Fe and the four corners, and then onto California: Santa Barbara, Pismo Beach, Solvang, and then a long stint in Los Angeles. Compared to the east coast, you just can’t beat the nature that the West has to offer. We had our fill of hiking and oceanscapes, plenty of wildlife (Humpbacks! Coyotes! Pelicans!), and great seafood and Mexican food. We tried as much as possible to travel without relying on a car (I recommend the sleeper Amtrak from Albuquerque to Los Angeles), but it wasn’t easy.

Maybe Jim Morrison was right in that “the West is the best” back in 1965, but it hasn’t held up. My partner’s blog says it all. We always thought we might return to live on the West Coast, but our vision of what we think California should be is over, finished. It went in another, less interesting and unauthentic direction long ago. As Farhad Majoo wrote, “It’s the end of California as we know it. I don’t feel fine.” But I’m over that now. As you can surmise from some of my past blogs, I think I’ll just stay right where I am.

On the trip, I read a few books that resonated well with the Western scenery. The first, The Nutmeg’s Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis by Amitav Ghosh, who wrote the book during the most constraining lockdown period of the COVID-19 pandemic and the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, will leave you spent, sad, and seething. He begins by describing how the colonial forces of the Netherlands, under the guise of the Dutch East India Company, purposefully and systematically eliminated the indigenous peoples living in the Banda islands, an Indonesian archipelago, to monopolize the nutmeg trade.

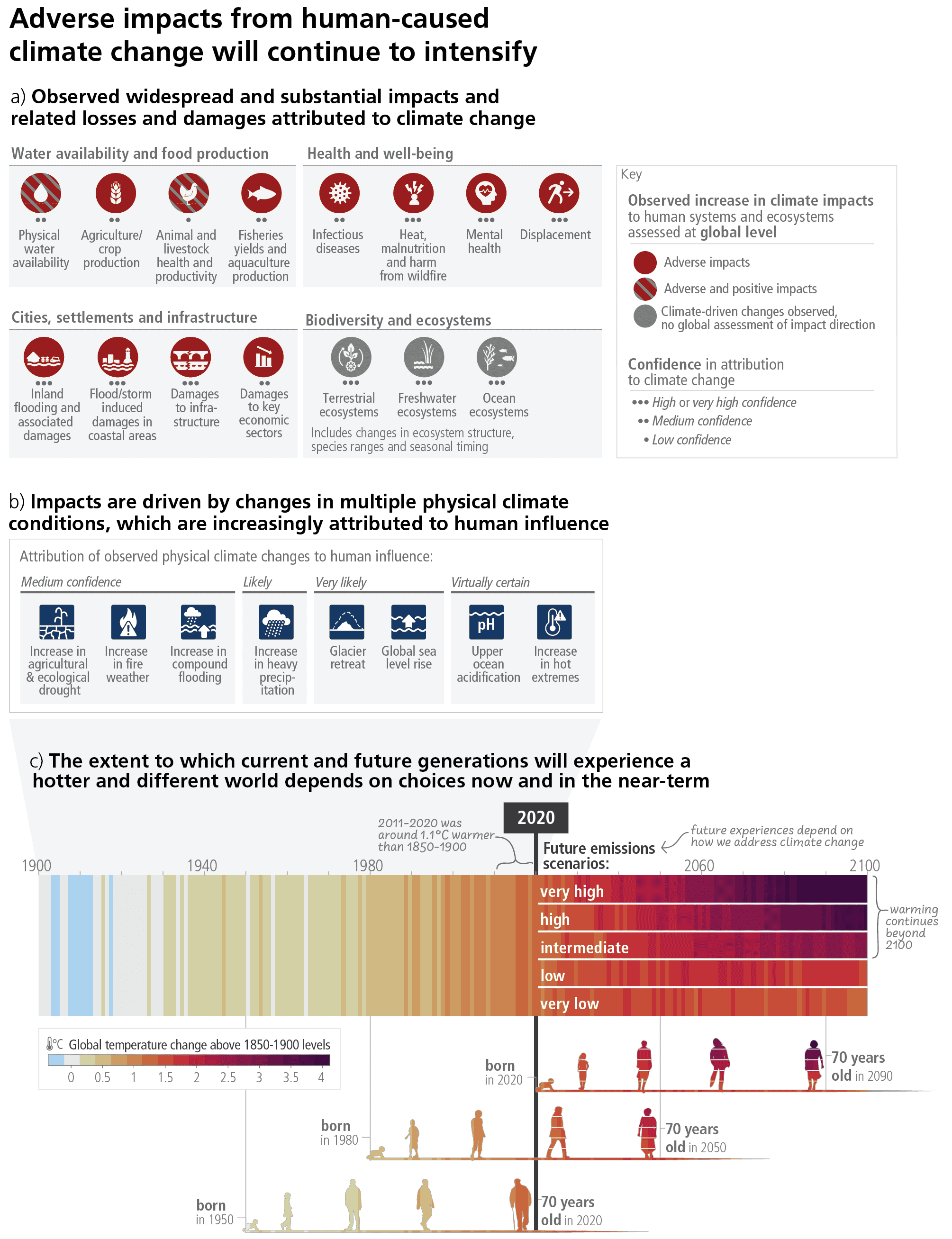

He further discusses the historic brutality of colonists on different landscapes through a process called “terraforming” and how that long history has contributed to the climate crisis we face, some disproportionately. He relates this genocide of the Banda people to other peoples, like the Western colonial forces in North America that obliterated Native American tribes and their way and essence of living. I was reading this book as we drove through the beautiful Navajo Nation. Witnessing places like Monument Valley and Canyon de Chelly leaves you awestruck, wondering, who deserves to watch over this land for all of us and future generations? They do.

Driving through their vast lands was devastating and inspiring, and I kept thinking about how this landscape is, at the same time, untouched and brutally altered. The Ken Burns’s documentary, An American Buffalo, punctuates how much has been forcibly taken from the Indigenous Peoples of this land. The Native Peoples. If you do watch the documentary, which I highly recommend, be prepared to be heartbroken over the long, dark history of “how the West was won.” As Dayton Duncan wrote in the New York Times:

“The story of what happened to the buffalo was a triple tragedy: for the animals, who were mercilessly slaughtered by the millions to feed an insatiable industrial demand for their hides; for the vitality of the Great Plains ecosystem that depended on them; and perhaps most profoundly for Native people, who were simultaneously dispossessed of their homelands, confined to reservations and deprived of the animals that had fed their bodies and nourished their spirits for untold generations.”

I also read Sea of Cortez by John Steinbeck and Rachel Carson’s The Sea Around Us. Both books were written in 1951 but still resonate with the perils of oceans today. Carson’s book was part of an ocean trilogy, and in this book, she dug into the science to help untangle the mysteries of the deep oceans. She mentions how the world was getting warmer, and sea levels were rising, but both were part of a “normal” process. Little did she know what was coming... I wouldn’t recommend them unless you like reading historically about what knowledge we knew then, as compared to what we know now.

On our holiday, I spent much time staring at the great Pacific Ocean – its vast blueness, mystery, and fierceness. While these books are a bit on the old side, it is fascinating to read how both authors were meticulously describing what we knew about oceans at that time. I still feel we know too little, and interestingly, many of us who work on food systems pay little attention to oceans. Instead, we spend a lot of time focusing on the land. This is ironic, being that land covers only 29% of the earth, whereas water covers 71%.

Yet, oceans and waterways matter a lot for food security. According to FAO, in 2022, the world produced 185 million tons of aquatic animals, and the net worth of the trading of aquatic food products was $195 billion. Even more so, 62 million are employed in the sector. This industry is nothing to sniff at!

Interestingly, in the past couple of years, aquaculture surpassed capture fisheries for the first time, contributing 51% of total fish production. But we have to figure out how to ensure both aquaculture and fisheries are managed in environmentally sustainable ways, and we must begin to care for our oceans and waterways if we want to ensure we have a rich biodiversity of blue foods in the future. My colleagues Roz Naylor, Safari Fang, and I wrote a paper reviewing six countries’ aquaculture policies and what could be learned from them. In these case studies—covering the EU, Bangladesh, Zambia, Chile, China, USA, and Norway—we highlight the need to find the right policy balance between semi-subsistence farms, small and medium enterprises, and large-scale commercial operations, particularly in low-income settings. The cases also highlight the importance of addressing aquaculture disease pressures and misuse of antimicrobials in many parts of the world and the challenges of establishing nutrition-sensitive aquaculture policies and incorporating aquaculture directly into food policy and global food system dialogues and action.

While in California, I ate plenty of blue foods, especially bivalve foods. Oysters, clams, crabs—you name it, we ate it. Did you know Pismo is the clam capital of the world? Bivalves are delicious, nutritious, and environmentally sustainable. I got my fill, and now I can go home.