FOOD BYTES IS A (ALMOST) MONTHLY BLOG POST OF “NIBBLES” ON ALL THINGS CLIMATE, FOOD, NUTRITION SCIENCE, POLICY, AND CULTURE.

I thought I would write up the November Food Bytes before the onslaught of publications leading up to the COP28 climate meeting takes place. Here is the roundup!

Some interesting articles and books:

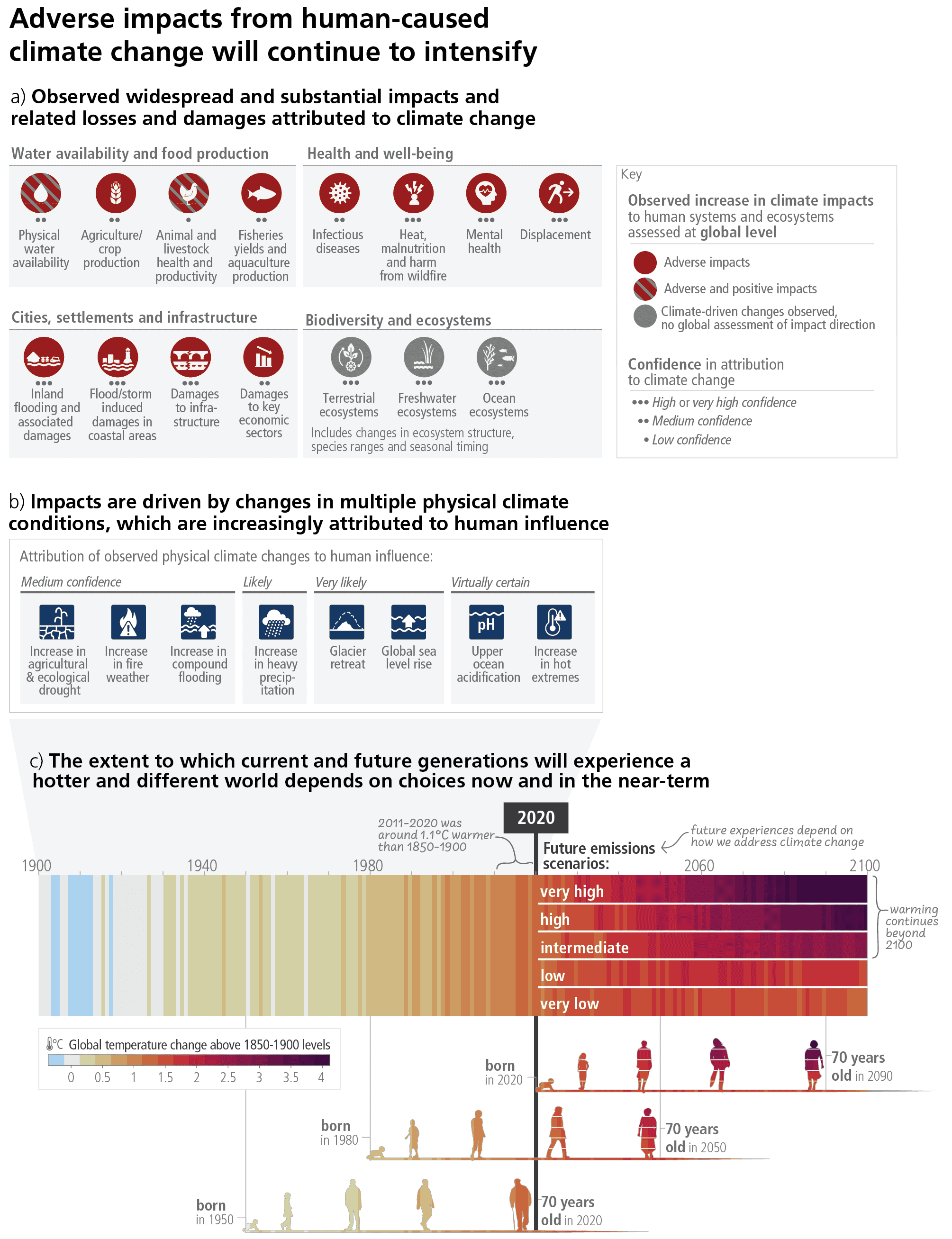

The great “godfather of climate science,” Jim Hansen, also a Columbia colleague, has put out a paper with colleagues arguing the planet may be warming faster than previous estimates have indicated by measuring “climate sensitivity” – measuring the earth’s warmth via atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations. Global CO2 levels hovered around 280 parts per million in the pre-industrial age. Now, they are above 400 ppm. Not everyone agrees with this paper, but no matter, Hansen is sending us clear warnings.

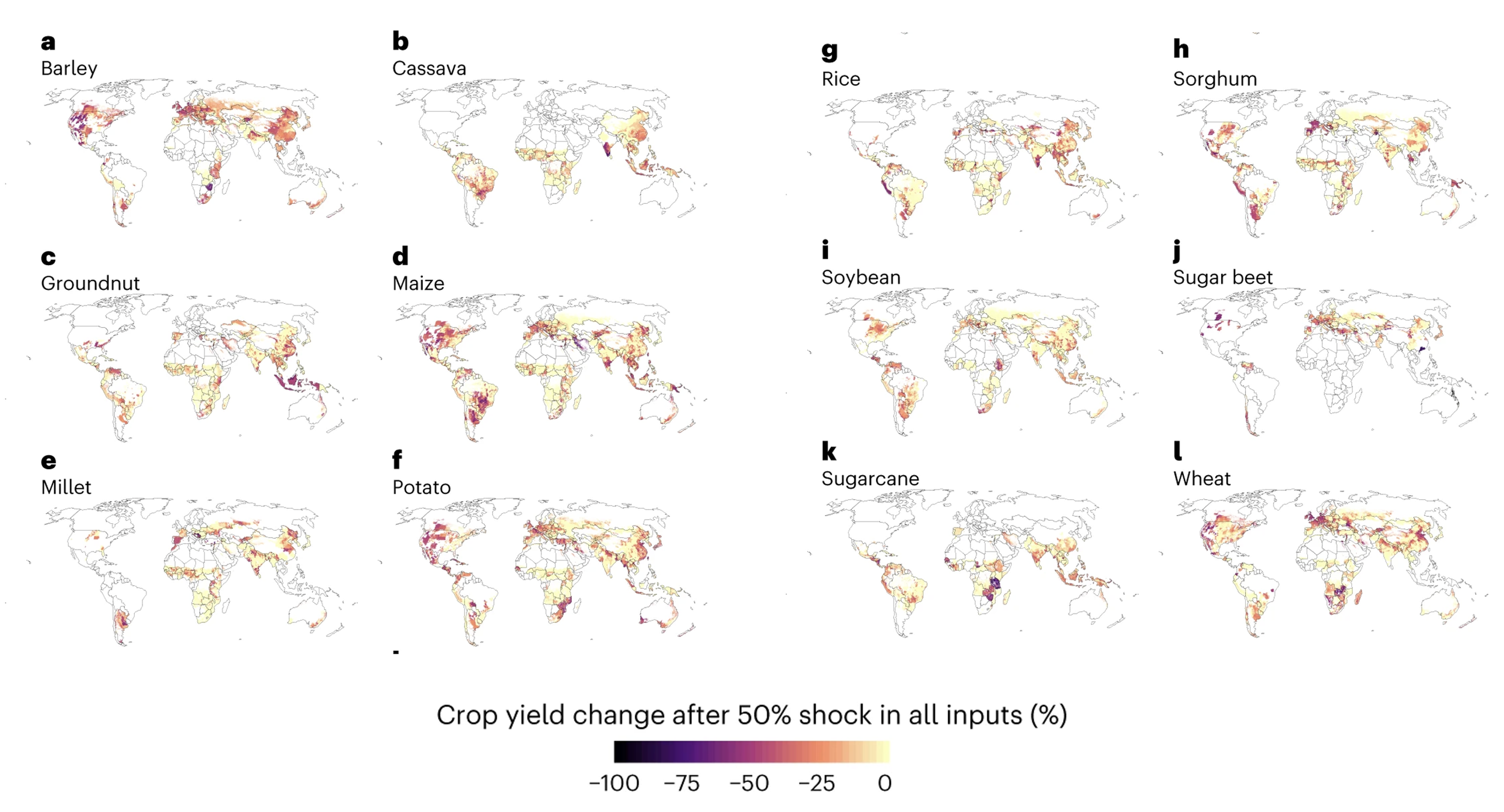

We are more and more worried about how resilient our food systems are in the face of extreme events and shocks, be they climate, environmental, or political. This paper examines the impacts of crop yields related to several agriculture input shocks – nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, machinery, pesticide, and fertilizer. Industrialized agriculture systems depend on these inputs, and often, they are imported from other countries. When combined, as you can see in the figure, some areas showed decreased yields for some but not all crops. The yields of barley, maize, potato, and wheat decreased heavily in the western United States. Barley, maize, millet, potato, sorghum, and soybean yields all decreased in northern Argentina, while barley, maize, potato, and wheat. To some extent, sugar beet also saw large yield decreases in Central Europe. Rice yields, in turn, decreased heavily in Thailand, Vietnam, and the southern part of India.

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/s43016-023-00873-z/figures/3

My friend Bill Dietz, the Director of Sumner M. Redstone Global Center for Prevention and Wellness at George Washington University, and I just published a paper on how the U.S. agri-food sector can contribute to climate change mitigation. The paper is timely for the upcoming COP28 meetings. The U.S. needs to step up!

A new book on the political economy of food system transformation co-edited by Danielle Resnick and Johan Swinnen has been jointly published by IFPRI and Oxford University Press. The summary follows: “The current structure of the global food system is increasingly recognized as unsustainable. While the need to transform food systems is widely accepted, the policy pathways for achieving such a vision often are highly contested, and the enabling conditions for implementation are frequently absent.” Check it out and download it for free here.

Some interesting reports:

Every year, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, also known as FAO, releases two flagship reports: the SOFI and the SOFA. The SOFA just came out this past week and focuses on the “true cost of food.” That means they assess the hidden environmental, health, and social costs of producing our food. What is their final assessment? Global hidden costs of food amount to 10 trillion dollars, with low-income countries bearing the highest burden of hidden costs. Yikes.

The Global Alliance for the Future of Food released an interesting analysis in this report calling for food systems to wean off fossil fuels. Wouldn’t that be nice….They argue that food production, distribution, processing/packaging, storage, and sales consume about 15% of all fossil fuels generated annually. They argue that the fossil fuel industry holds a lot of sway with governments, making it difficult to “extract” (sorry for the pun) their influence or hold them to account.

A report by the group I-CAN, which looks at the integration of climate and nutrition, came out. It is interesting…nothing new…and much built on the long scientific publications already out there, but I supposed putting it in a layperson report gets the message out there.

Some interesting listens:

Vice did an “expose” on how the Italian mafia has taken over food systems in Italy. Having lived in Italy and interested in Italian deep food traditions, I watched it. The document is not well done, with much speculation and little evidence beyond a few interviews. If it is even true, I wasn’t convinced by this documentary.

John Oliver’s Halloween episode focused on the issues of child labor related to producing chocolate – focusing on Ghana and the Ivory Coast, where roughly 60% of it is produced. A lot of the material is borrowed from Netflix’s Rotten series. Still, the message is clear that many children (1.56 million) are engaged in cocoa production stemming from insufficient wages paid by massive confectionary companies to smallholder farming families working or owning cocoa farms, leaving them in gut wrenching poverty. Such a tragedy. I don’t think John Oliver adds much to the debate – if you want a quick watch, go to the Netflix episode.

In their usual snarky, pick-it-to-pieces style, Mike and Aubrey of the fantastic Maintenance Phase podcast sink their teeth into Ozempic, the weight loss diabetes treatment drug. It's well worth listening to the latest.