This is a cross-posted blog from the Berman Institute of Bioethics’s Global Food Policy and Ethics (GFEPP) blog. It was written by Leslie Engel, MPH, a Science Writer Consultant for the GFEPP.

Americans have more ways than ever to shop for the ingredients needed for their meals. This was not always the case. Prior to the first self-service grocery store opening over a century ago, shoppers had to rely on clerks to retrieve and package items for them. Since then—aside from the invention of scanners and self-checkout—the grocery shopping experience has remained largely unchanged. It’s an industry ripe for disruption, and tech companies have seized upon this.

Rowan Freeman, Unsplash License

Enter grocery delivery services. These companies make lofty promises—to eliminate the hassle of grocery shopping, meal planning, preparation, and even the act of cooking itself—while also being good for you and the environment. And more Americans than ever are now using them.

I worked as a recipe manager for a leading grocery delivery startup whose mission is to make healthy eating easy by using artificial intelligence (AI) technology to predict customer food preferences. As a professionally trained chef with a background in public health, I was fascinated with the ability of such services to seamlessly deliver top-quality, nourishing, and sustainable products and recipes to customers, potentially as another avenue to improve health and wellbeing through home cooking. However, as I developed yet another recipe involving ground beef, I began to question how healthy this industry really is, both for ourselves and for our food system.

Convenience, for a price

Convenience, safety, and accessibility are the main appeal of these delivery services. This was especially evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, when many consumers turned to delivery to avoid in-person shopping. In theory, this means that more people will have better access to food, especially those with health, mobility, or other constraints. However, convenience comes at a price, and grocery delivery services pass this cost onto consumers in the form of markups, service, and delivery fees. Additionally, increased food costs due to inflation likely render this convenience financially out of reach for those most in need.

Reduction in greenhouse gas emissions?

There’s some evidence that grocery delivery could be more environmentally friendly than hopping into the car because it reduces greenhouse gas emissions. A study in Washington State demonstrated that it may be more efficient for a fully stocked truck to deliver to multiple households in the same neighborhood rather than individuals driving to the store themselves. But this is a best case scenario. The biggest emissions reductions would require households to cluster their orders together and forgo specific delivery times, thus reducing the convenience factor and the main selling point of such services.

Tim Mossholder, Unsplash License

Reliance on California’s Central Valley

Twenty-five percent of our nation’s food is produced in the Central Valley of California. The area is so integral to business that the company I worked for hired someone specifically from the region to oversee produce sourcing. But its agricultural future is in peril: water is scarcer than ever, severe droughts related to climate change have diminished groundwater stores and decimated crops, and intensive farming practices exacerbate the problem.

Crop failures or shortages were a huge sourcing and supply chain headache with trickle down effects. Customers often complained about receiving an inferior product, or one not as uniform as what they were accustomed to. Receiving a last minute vegetable “swap” presented a whole new set of customer challenges: I don’t like the cauliflower that replaced my broccoli! And how am I supposed to cook this?

The end result was often wasted food, as evidenced in the customer comments I analyzed. Food wasted at the household level is especially egregious because it squanders all the resources that went into growing, processing, packaging, and shipping it. In the U.S., between 73 and 152 metric tons of food is wasted somewhere along the supply chain annually. About half of that waste is happening at the household or food service level. And worldwide, food waste contributes 8% of human-generated greenhouse gas emissions, making it a significant contributor to climate change.

Technology

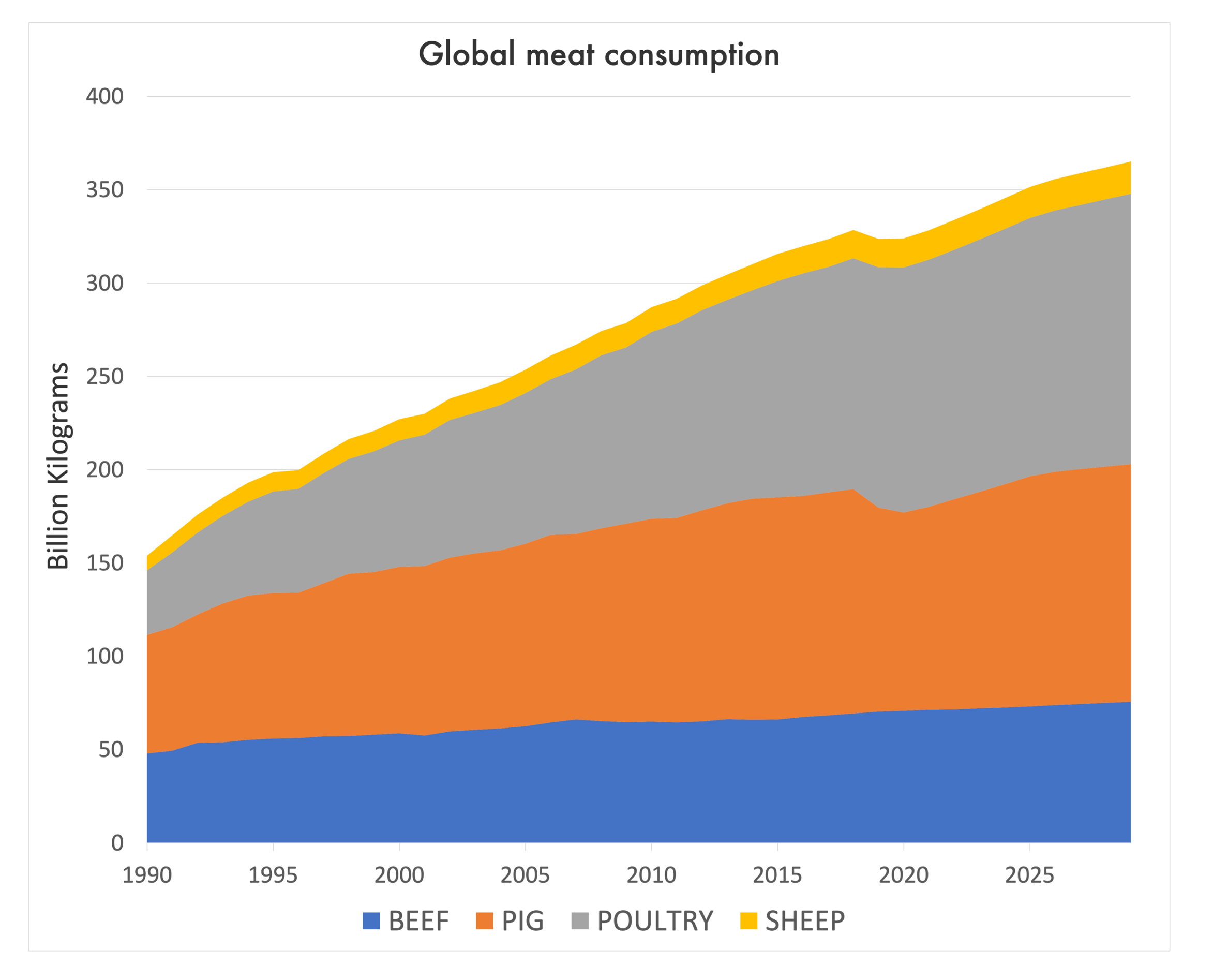

When customers rated a product or recipe, it became a data point used to further refine the AI, which then “decides” what product or recipe will go into their next delivery. You’ve no doubt seen the effectiveness of this technology in eerily relevant pop-up ads. Similar to how AI learns which ads you are most likely to click on, it can also learn which foods you’re going to enjoy or not. Like that hamburger? You shall receive more ground beef! It becomes a feedback loop designed to retain customers and increase profits, but not necessarily improve your health or the environment.

Looking Ahead

I still believe that grocery delivery services and the technology that drives them are the way of the future and can be a positive force within the food system. AI can potentially be used to improve diets, not just increase profits; researchers have harnessed this technology to help people grappling with obesity and diabetes to eat better.

To improve access for everyone, the U.S. government should make it easier for grocery delivery companies to accept Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).The USDA is currently piloting a program that enables SNAP recipients to purchase groceries online from select retailers. Incentives should also exist for companies to waive delivery and service fees for SNAP recipients.

In addition, produce should be sourced regionally when possible. Shorter transit distances from farm to fridge mean less greenhouse gas emissions and fresher, more nutritious produce with a longer shelf life that’s less likely to be tossed. Fresh Direct offers a selection of local produce and more services should follow suit. The increased demand could help boost struggling regional agriculture and decrease demand on the imperiled Central Valley. Finally, the biggest thing missing from this new grocery shopping experience are people. AI may be “filling” your cart, but humans still harvest, process, pack and deliver everything we eat for low wages in unsafe working conditions. The pandemic has revealed that the meatpacking industry will go to great lengths–at the expense of humans–to maintain production and profits. Most recently, dozens of children were found to be illegally working as sanitation workers in meatpacking plants. By further alienating ourselves from where our food comes from, we’re less likely to see the value in the people behind the scenes making sure your fridge is full.

Leslie Engel, MPH, is a Science Writer Consultant for the Global Food Ethics and Policy Program.