As world leaders meet to discuss grand global challenges, like climate change, over champagne cocktails this week here in NY, my friend and colleague, Chris Barrett and company asked to write about what I think are the main barriers or challenges to a just, sustainable dietary transition. Hmmmm. Where to even start?

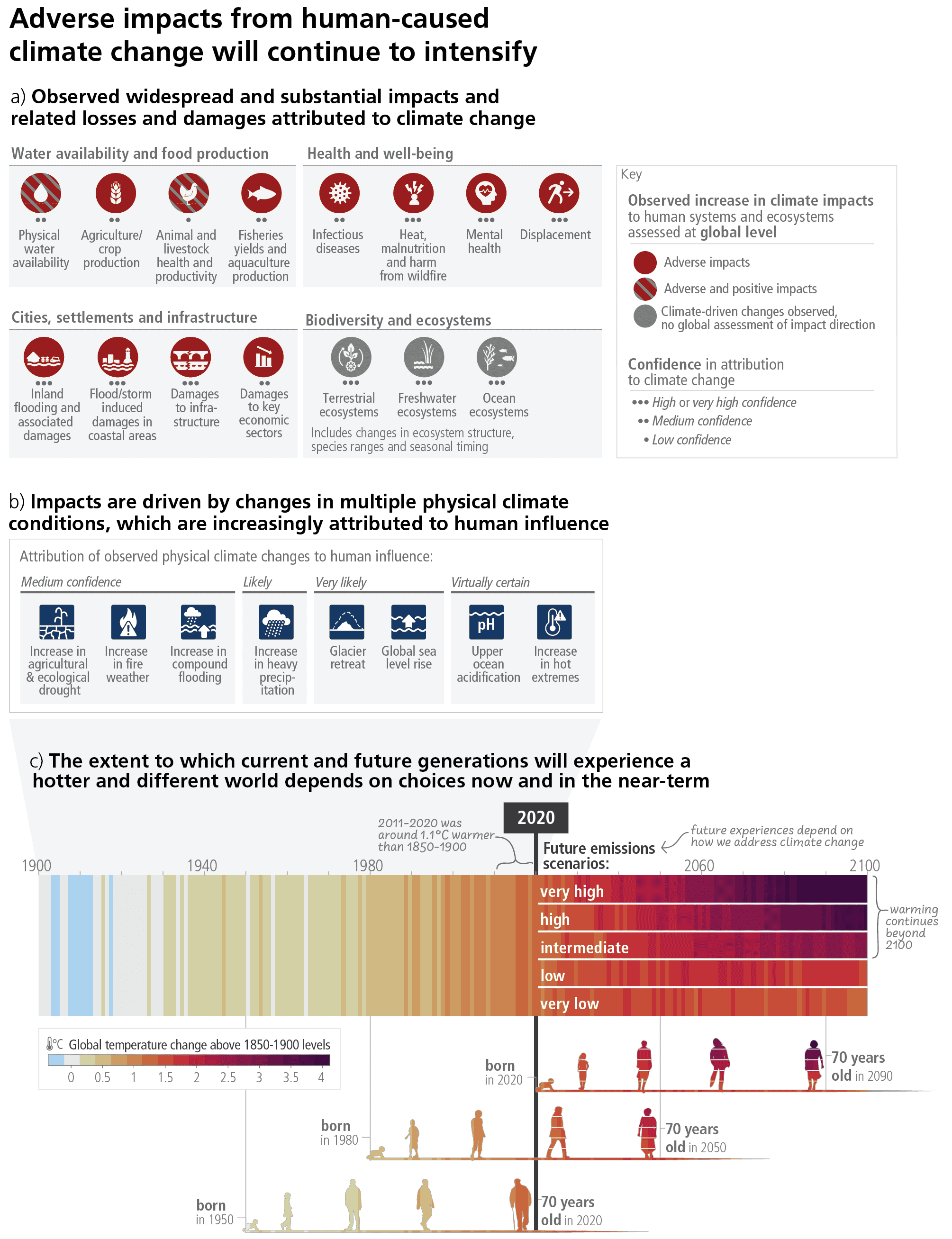

The overarching major challenge is the inequities in the ability of many people to access (physically, economically, and socially) what is considered healthy, safe, and sustainable diets. Ironically, many of these same people are the food producers for the world. Accessing these diets and adapting will only get more complex if we stay on a business-as-usual course in the context of climate mitigation and adapting to climate-related extreme weather events.

There are many reasons for this lack of access that could cut across inefficiencies across food supply and environments and demands for specific kinds of food that put the world on a dangerous course. However, there are a few barriers that I would like to highlight. This summary focuses on food systems. However, many systems and sectors are responsible for meeting this goal, such as health, economics, education, and urban/rural development.

The first challenge is unrealistic goal and recommendation setting. Goals such as the Sustainable Development Goals provide a universal road map for how we want the world to be in seven years. Still, not every goal is relevant, meaningful, or a priority for every country. Recommendations for food system transformation are often made as generalities, not articulating who is responsible, for what, and by when. They also do not indicate how these recommendations can be translated into action ‘on the ground’ in the context of established interests and constrained budgets.

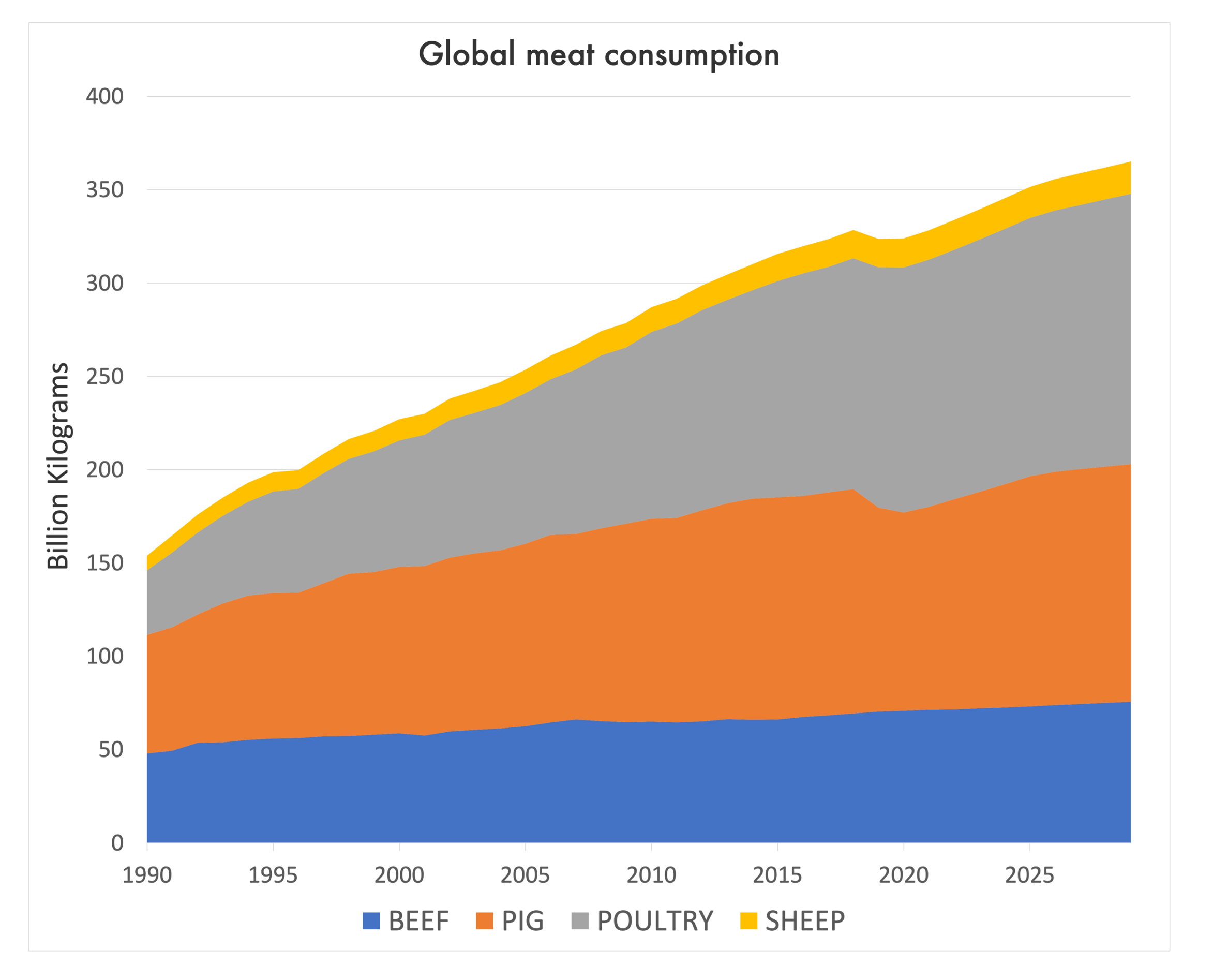

The second challenge is data gaps. High-quality analytical methods and tools to collate, curate, and analyze data across food systems; integration of data sets across disciplines; and new empirical research to solve the grand challenge of sustainable development (Fanzo et al., 2020). These data gaps bring about difficulties in navigating unintended consequences or trade-offs. While there are many gaps across food systems science, I focus on diets here.

We remain unclear on what people consume, why, and their barriers to accessing healthy, sustainable diets. Global dietary intake data that are nationally and subnationally representative remain sparse. Most countries do not consistently and systematically collect individual dietary intake data, and the existing data are often based on models relying on household expenditure and consumption survey data, food balance sheet data, or data from subpopulation nutrition surveys. Although these modeled estimates may give us a sense of dietary intake and patterns of consumption, they are an uncertain substitute for robust, representative individual dietary intake data reflecting recent consumption patterns at a national level, particularly in low- and middle-income contexts. Collecting robust longitudinal dietary data would allow researchers and policymakers to understand better how diets change over time and why.

The third challenge is the politics across food systems governance. As one example, the United Nations Food Systems Summit (UNFSS) and its stock take in July 2023 is not without uncertainties and controversies, with rumblings of it all being grandiose political wonk talk. With summits, there are always questions about impact. Will all stakeholders be included? Will the needs of the vulnerable and marginalized be prioritized? Will there be a sense of urgency to scale up investment? Will there be any accountability mechanism to track commitments and hold those to account who fall behind? If this is the mechanism for food systems change and for governments to engage, these questions are critical to understand and act on.

While addressing effective governance is a sticky issue, more and more, we as researchers must engage in this space if we are to see evidence come to bear in policy- and decision-making.