This piece was originally published as a commentary in Communications Earth & Environment.

Policymakers worldwide are paying more attention to the whole food system—production, processing, distribution, consumption, and the link to food security and farmers’ livelihoods. For example, in 2021, the United Nations Food Systems Summit opened the dialog between stakeholders from multiple fields and encouraged national actions to transform the food system. Most recently, the 28th Climate Conference of Parties resulted in a Declaration on sustainable agriculture, resilient food systems, and climate action. While these political commitments are essential foundations of change, research is needed to provide a scientific basis to support policy decisions and help design solutions that fit community needs.

Recent shocks, including the COVID-19 pandemic, conflict in Europe, and the impact of climate change, are pushing global food systems to breaking point. Around 42% of the world’s population cannot afford a healthy diet that meets nutritional needs. We are witnessing political attention on food systems, with the United Nations hosting the Food Systems Summit in 2021, which brought together more than 100 countries and represented an opportunity to strengthen food system resilience. Yet, we must address challenges that inhibit progress.

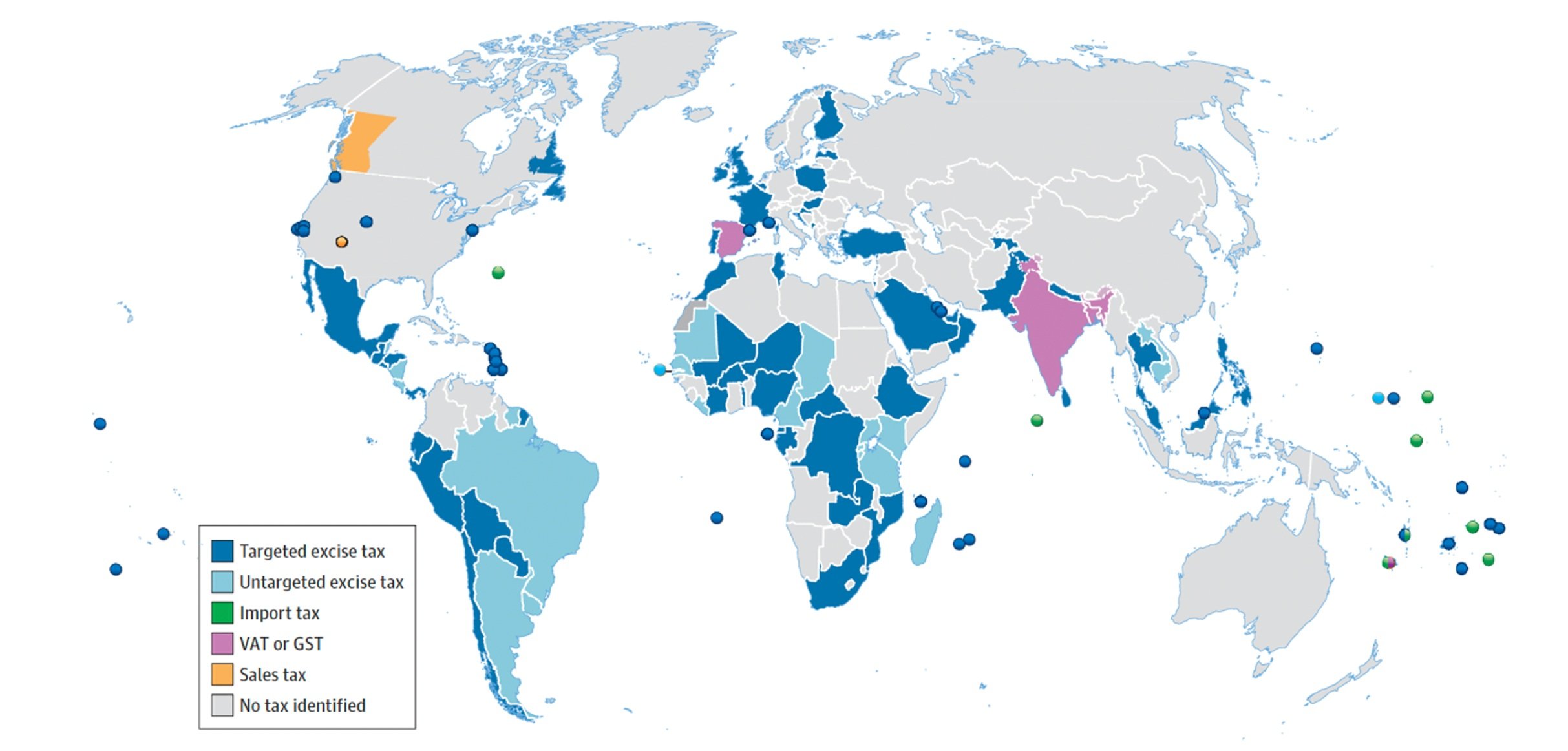

The first challenge is to provide equitable, physical, economic, and social access to healthy, safe, and diverse diets. Solutions across food supply and demand have been proposed and implemented to address access constraints across local contexts. Some examples of solutions include homestead gardening, biofortification, reformulation of food products to remove unhealthy ingredients, taxes on sodas and highly processed foods, front-of-the-pack labeling to signal the healthfulness of food products to consumers, national food-based dietary guidelines, and food-related safety nets. However, many of these solutions have not been scaled sufficiently to have multiplier and positive impacts.

The second challenge is to address the power asymmetries in food policy and politics. Private companies involved at every stage of food supply chains are increasingly concentrated and wield significant economic and political power. Some companies continue to generate massive profits at the expense of public health and environmental sustainability, leading to a lack of trust from the other stakeholders. The disaccord jeopardizes an inclusive momentum to galvanize the transformation of the global food system.

Data are needed to assess the performance of food systems, determine where and how to intervene, and assess unintended consequences or trade-offs of tried solutions, which constitutes the third challenge. Sixty food system experts have developed the Food Systems Countdown to 2030 Initiative to guide and hold public and private sector decisions to account. The Countdown monitors 50 indicators across food systems related to diets and nutrition, climate and environment, livelihoods and equity, governance, and resilience. The indicators can track the holistic nature of food systems, align decision-makers around crucial priorities, incentivize action, sustain commitment, and enable course corrections. The Countdown shows that no single region has a monopoly on food system success.

Every region and country have room for improvement, and countries can learn from each other. Governments must step up and restore the power balance and play a more active role in shepherding food systems in positive directions. Investment in place-based solutions is critical to understanding what works, where, in what context, and for whom.